TOPICS

For those new to this issue it’s best to know these terms before reading.

8) Regret rates and long-term mental health

Even though data on trans people post medical transition show continuing high rates of mental health problems, higher suicide risk and physical health problems, it is often reported that dysphoria is mitigated by transition and that mental health generally improves. A review confirming this was done by Cornell University. All of the abstracts can be found here. A thorough review of these studies and the impact of transition on mental health and suicide is done on this website in this section. The overall message is that transition does seem to improve mental health. Studies with less lost to follow ups, as well as some review studies, however, (Adams 2017, Marshall 2015) don’t seem to show any improvement is suicide risk. This indicates transition is not a fix all. However, the Cornell review does confirm very low regret rates (3.4% at the higher end) in populations of adults who were treated at a time with much more pressure not to transition due to stigma and under a thorough evaluation model.

Regrets following gender transition are extremely rare and have become even rarer as both surgical techniques and social support have improved. Poling data from numerous studies demonstrates a regret rate ranging from .3 percent to 3.8 percent. Regrets are most likely to result from a lack of social support after transition or poor surgical outcomes using older techniques.

There is generally a strong desire to paint social support and access to medical transition as sole factors in mental health. However, unfortunately even trans people in very supportive families and communities retain much higher rates of problems than age matched control groups.

While evidence suggests regret rates have historically been very low in the past, the research studies often have majors flaws.

Here, a review highlights some of the problems involving tracking mental health and regret rates in earlier studies. The Guardian summarized the results of a review of “more than 100 follow-up studies of post-operative transsexuals” by Birmingham University’s Aggressive Research Intelligence Facility (ARIF):

ARIF, which conducts reviews of healthcare treatments for the NHS, concludes that none of the studies provides conclusive evidence that gender reassignment is beneficial for patients. It found that most research was poorly designed, which skewed the results in favor of physically changing sex. There was no evaluation of whether other treatments, such as long-term counselling, might help transsexuals, or whether their gender confusion might lessen over time.

Of particular concern are the people these studies “lost track of.” As the Guardian noted, “the results of many gender reassignment studies are unsound because researchers lost track of more than half of the participants.” Indeed, “Dr. Hyde said the high drop out rate could reflect high levels of dissatisfaction or even suicide among post-operative transsexuals.” Dr. Hyde concluded: “The bottom line is that although it’s clear that some people do well with gender reassignment surgery, the available research does little to reassure about how many patients do badly and, if so, how badly.”

This commentary provides further review:

The final August 2016 “Decision Memo for Gender Dysphoria and Gender Reassignment Surgery” was even more blunt. It pointed out that “Overall, the quality and strength of evidence were low due to mostly observational study designs with no comparison groups, subjective endpoints, potential confounding (a situation where the association between the intervention and outcome is influenced by another factor such as a co-intervention), small sample sizes, lack of validated assessment tools and considerable loss to follow-up.” That “loss to follow-up,” remember, could be pointing to people who committed suicide.

And when it comes to the best studies, there is no evidence of “clinically significant changes” after sex reassignment:

The majority of studies were non-longitudinal, exploratory type studies (i.e., in a preliminary state of investigation or hypothesis generating), or did not include concurrent controls or testing prior to and after surgery. Several reported positive results but the potential issues noted above reduced strength and confidence. After careful assessment, we identified six studies that could provide useful information. Of these, the four best designed and conducted studies that assessed quality of life before and after surgery using validated (albeit non-specific) psychometric studies did not demonstrate clinically significant changes or differences in psychometric test results after gender reassignment surgery (GRS).

A. Despite low regret, rates mental health problems remain high, indicating transition is not a fix-all for gender dysphoria

Even with very low recorded regret rates in the transgender population, most studies show continuing high rates of comorbid conditions and suicide risk relative to controls. Even the Olson-Kennedys (Johanna and Aydin, a married female/FtM couple and affirmative model activists) acknowledge gender dysphoria is often not actually cured by medical transition, only managed and that problems remain. In this way gender dysphoria does have some similarities to body dysmorphic disorder where cosmetic surgery do not actually alleviate distress long-term and mental health problems and anxiety about appearance continue.

(Gender Odyssey, 2017):

If you are a parent as well, one of the concerns is going to be regret. I think as mental health providers we have a different relationship…But I think that we need to reorganize and think about what does regret mean? And where does it come from? When I think about who is talking about regretting transition or who is detransitioning, or retransitioning, or having a lot of those conversations. When you really whittle down, like what’s happening for that person, their gender identity has not changed. It was never and is not about gender identity, it is about, “I still have gender dysphoria. I didn’t know I was still going to have gender dysphoria. I didn’t know that I would still struggle in these ways and these places. I didn’t know that. I thought that I had gender dysphoria and would have intervention and I would feel better. And I don’t feel better.”

And so, people then make decisions to detransition because if, “I feel bad on either side, life is perceived as easier if I’m not seen as a trans person, than if I am seen as a trans person. And so, it is not about, “I was wrong about my gender. It’s about, “I am so surprised that I’m still kind of struggling a little bit and having a hard time but I still have gender dysphoria.”

Then if we look at people who detransition or retransition, a lot of those folks transitioned a) in adulthood, b) ten or more years ago. And so, the conversation really was about, you have this problem, we’re going to do this thing and then you won’t have this problem anymore…and so a false paradigm was set up. And so those are the folks that are very loud. And those are the folks who have a lot of opinions. And those are the folks who have a lot of opinions about people transitioning in earlier in life…It’s way harder to be inauthentic than to be authentic and have struggles.

The below quote was a response to a mother of a 16-year-old. The youth started to transition at 14 and the young person gets depressed after each transition step following a honeymoon period.

It is this idea around, there’s ups and downs. There are these honeymoon experiences. So, someone has a lot of gender dysphoria. They are able to start hormones, for trans masculine people, or testosterone. Testosterone starts impacting and creating changes relatively quickly. And so, there is a decrease in gender dysphoria. “My voice is too high. I don’t have any facial hair.” Like that stuff starts happening relatively quickly. So, gender dysphoria organized around physicality decreases. And so, there is kind of a honeymoon period. But all honeymoons, unfortunately, have an end. And gender dysphoria will increase again. And so, things will be more difficult. Your kids may be struggling again. And then chest dysphoria becomes a real necessity. And not only a desire, but a necessity.

And so, they will be struggling a lot because the more they show their body the more obvious it is they have breasts, right? To themselves and other people... So, there is an up and down, And I have a very strong belief that gender dysphoria, in a variety of forms, is a lifelong experience. If your child had chest dysphoria, they will not have chest dysphoria again after they have chest surgery.

So, there are pieces that are very addressable. But there are pieces that are just an ongoing life-long experience. (proceeds tell parents that this is likely to keep happening with their child and the youth will continue to dip into depression post each transition step and that GD never fully goes away) genital dysphoria will be next when they negotiate relationships…In my belief it is always there. Is it always present? Is it going to be something that your kids’, boys or girls or non-binary are going to have to navigate for the rest of their lives? I really do believe that. And I’ve had opportunities to talk to people who have transitioned 20 or 30 years ago. And they say that has absolutely been their truth and their experience.

Johanna Olson-Kennedy concurs this reality on a Straight Talk MD podcast: (link down)

And that being said, I don’t think that we, that I, would not like to promote the idea that social transition is the panacea, and that it’s going eradicate gender dysphoria, because it’s not. Gender dysphoria is the distress that arises from in congruence, and the in congruence is never gone. You can’t go back and unassign your gender or sex at birth. You can’t do that. And so, gender dysphoria shows up in a lot of ways. And we have to be mindful of that because what happens often is parents say “Well, we let you go on hormones, and we let you socially transition, then why are you still depressed?” or “why are you still anxious?” or “Why are you still self-harming?” And, as cisgender people, we can’t understand what it means to have gender dysphoria because we don’t have it, and so we have to be mindful, as clinicians to look for it, and see how it waxes and wanes over time.

And I think that we underestimate- so someone could be completely socially transitioned in childhood, they could go onto feminizing hormones at an early age, and they’re going to navigate high school when sexuality is sort of at a premium, with genitals that may or may not be what they resonate with, or what feels right for them. And so that’s going to be a big place of gender dysphoria for people, is, at the end of the day you have different challenges when you are non-disclosed, you’re completely perceived as your authentic self, but you are really restricted from entering into intimate spaces. Both with friends but also with potential partners, and that plays a big role in people’s lives, especially teenagers.

When discussing a client who had gone through transition, Michelle Angello (Gender Odyssey, 2017) the nagging feelings his patient has of being incomplete:

And for some it can be the panacea and for others, again its complex. And so there are going to be other things and now we get the opportunity to work on them.

This detransitioner also notes that despite low regret rates he observed:

I’ve seen the statement made many times that “the rate of regret for gender transition is very low”, generally quoted between 1 -3 % or so. This information is used as evidence that we should not be so concerned with the problem of detransition. People identifying with a certain gender and wanting to transition is enough proof that transition is right for them, and therefore there is no need for any in-depth screening. If someone identifies with a certain gender and wants to transition then clearly that is the right thing, as evidenced by low regret rates. Also, there is no reason to look at different ways to deal with dysphoria, because we have this great treatment that already works.

However, there are several problems with this which are:

-The reported measures of regret rates don’t actually measure regret rates.

-Regret rates are not the sole measure of good / bad outcomes.

-The demographics of transitioners today are not the same as those in the past.

-Gender transition and improving people’s quality of life, doesn’t mean there aren’t less invasive ways to get the same improvement.Because I transitioned 20 years ago, I know many MtF transitioners that were in my cohort 5-10 years before. What I see is concerning. I am the only one out of them that has detransitioned, and most of them would not say that they regret their transition and continue to go by feminine pronouns and feminine names. In terms of life outcomes, I would say economically they are mostly doing well. However, socially they are struggling. Most of them are alone. I see a lot of social anxiety, people being unwilling to leave the house. In addition, they still continue to deal with dysphoria and have emotional difficulties.

This is not a good thing, some people would say these difficulties are due to oppression and by reducing this oppression it would reduce or eliminate these difficulties. I definitely believe that oppression is a large factor in some of the things that are awful about being transgender. I oppose those that intend to make the world worse for trans people. However, I do not think it is the sole source of these difficulties.

Here an FtM who is on an colostomy bag and has undergone 33 surgeries due to phalloplasty complications admits medical transition is not a panacea,

Many serious problems remain for trans people overall post transition. Without a control group it is impossible to know for sure how these individuals would fair if they lived in a world where medical transition was not possible (most of human history). There are some cultures where gender non-conforming people are accepted and they seem to do well without medical treatment (In Fiji and among the Zapotec). This professional research and consulting firm found low quality evidence for benefits of SRS and found weak evidence to support giving children puberty blockers.

Over the past two decades, Hayes, Inc., has grown to become an internationally recognized research and consulting firm that evaluates a wide range of medical technologies to determine the impact on patient safety, health outcomes, and resource utilization. This corporation conducted a comprehensive review and evaluation of the scientific literature regarding the treatment of GD in adults and children in 2014. It concluded that the practice of using hormones and sex reassignment surgery to treat GD in adults is based on “very low” quality of evidence:

Statistically signifcant improvements have not been consistently demonstrated by multiple studies for most outcomes. Evidence regarding quality of life and function in male-to-female (MtF) adults was very sparse. Evidence for less comprehensive measures of well- being in adult recipients of cross-sex hormone therapy was directly applicable to GD patients but was sparse and/or contradicting. The study designs do not permit conclusions of causality and studies generally had weaknesses associated with study execution as well. There are potentially long-term safety risks associated with hormone therapy but none have been proven or conclusively ruled out. (31,32)

Regarding treatment of children with GD using gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and cross- sex hormones, Hayes, Inc. awarded its lowest rating indicating that the literature is “too sparse and the studies [that exist are] too limited to suggest conclusions. (31)

B. Are regret rates increasing under the affirmation model with more transitions & people transitioning at younger ages?

Regret rates appear to be increasing

Acknowledging the results of the Cornell review, there is some anecdotal information that regret rates are going up, even among the numbers of adult transitioners who transitioned under the gatekeeping model. It’s difficult to tell as follow up studies have inherent major problems tracking true regret rates. Recent commentary also point to the fact that detransition rates may, in fact, be increasing and that the body of literature on detransition is fraught with methodological issues.

A scientist in Britain says this:

He said 40% of people who undergo vaginal reconstruction surgery experience complications as a result, and many need further surgery, and 23% of people who have their breasts removed "feel uncomfortable with what they've done".

He added: "What I've been seeing in a fertility clinic are the long-term results of often very unhappy people who now feel quite badly damaged.”

"One has to consider when you're doing any kind of medicine where you're trying to do good not harm, and looking at the long-term effects of what you might be doing, and for me that is really a very important warning sign."

This transgender healthcare expert is seeing more regretters:

Over the next six months, another six people also approached him, similarly wanting to reverse their procedures. They came from countries all over the Western world, united by an acute sense of regret.

Professor Miroslav Djordjevic:

At present, Djordjevic has a further six prospective people in discussions with his clinic about reversals and two currently undergoing the process itself.

Reattaching the male genitalia is a complex procedure and takes several operations over the course of a year to fully complete, at a cost of some R290,000.

Those wishing the reversal, Djordjevic says, have spoken to him about crippling levels of depression following their transition. Some have even contemplated suicide. "It can be a real disaster to hear these stories," says the 52-year-old.

Also from the same article:

Djordjevic, who has 22 years' experience of genital reconstructive surgery, operates under strict guidelines. Before any surgery, patients must undergo psychiatric evaluation for between one and two years, followed by a hormonal evaluation and therapy. He also requests two professional letters of recommendation for each person and attempts to remain in contact for as long as possible following the surgery. Currently, he still speaks with 80% of his former patients.

"I'm afraid what will happen five to ten years later with this person," he says. "It is more than about surgery; it's an issue of human rights. I could not accept them as a patient as I'd be afraid what would happen to their mind…"

Over the past two decades, the average age of his patients has more than halved, from 45 to 21…

As a result of the complications due the lowering of ages, he does not support those advocating for the medical treatment of children.

Djordjevic feels differently, and says he `has deep reservations about treating children with hormonal drugs before they reach puberty - not least because blocking certain hormones before they have sufficiently developed means they may find it difficult to undergo reassignment surgery in the future.

"Ethically, we have to help any person in the world starting from three to four years of age, but in the best possible way," he says. "If you change general health with any drug, I'm not a supporter of that theory."

These are profoundly life-changing matters around which he - like many in his industry - feels far better debate is required to promote new understanding. But at the moment, it seems, that debate is simply being shut down.

Michelle Angello (Gender Odyssey, 2017) had this to say in response to a story of a young female with a supportive family who was having regrets around transition and regretting she didn’t experience more of a chance to live in a female body unaltered.

I suspect that we are all probably going to experience that at least once probably multiple times if you are doing this work for any length of time. I think probably more so now because…people have the opportunity to have the medically necessary surgery that they were often times not able to have.

Ireland may have a higher regret rate than other places:

The country’s leading doctor who helps transgender people change their sex is now supporting three patients who regret having surgery.

Professor Donal O’Shea has told Extra “that their trauma highlights the need for proper support and resources to prevent post-operative remorse.

This country has a high rate of adults who regret treatment, he said:

While some transgender support groups do not wish to highlight the number of people who suffer from post-operative regret, Prof O’Shea believes it is important that people be made aware. He said three transgender people have died by suicide in the past five years, two had surgery and one was on hormone therapy…

‘The real conflict in this profession is seeing someone who makes a very positive transition, and that’s a humbling and amazing thing to see, and then at the other end, you also see some devastating outcomes. We are trying to come up with a situation where there is the least harm, but we cannot mitigate against all harm unfortunately,’ he said…

The experience of those who suffer from post-op regret and those who die by suicide highlights the need for resourcing and ongoing psychological and psychiatric support, and the need for input through each stage,’ he said.

Tania Marhsall, an autism expert and therapist, reports that she is witnessing more regretters among people who transitioned very young.

So I have seen some clients who did transition and regret it. I’ve seen some clients who transitioned and then retransitioned. So those clients that I have seen who regret their transition or retransitoned said that they felt that they were too young. That they were misdiagnosed as being trans rather than being autistic. For parents, teachers, therapists. School counselors, explore…

Serious consequences can result from an inappropriate transition, “I will never be able to have sex again. Ever.”

A recent British review found suicide rates of up to 18 per cent among people who had undergone gender reassignment surgery. Doctors from London's Portman Clinic say they see many patients who feel trapped in "no-man's land" after surgery, finding themselves with a body which is no longer recognizable as male or female. Psychotherapy, the experts believe, may have saved them from such a fate but few gender clinics offer it.

Reviews of the Monash clinic found psychotherapy was rarely, if ever, offered. While a patient would require a diagnosis as a "true transsexual" from two psychiatrists before being offered surgery, both opinions were from inside the clinic — one that operates under the fundamental ethos that surgery is the only cure.

Even if regret rates are low they are often very sad outcomes.

Twenty years after surgery that left him feeling like a "desexed dog", the grief can still overwhelm him. Now 42, Andrew tells The Sunday Age the operation he had as a confused 21-year-old has shattered him.

…For Andrew, it's the small victories that keep him going. "I will never be able to have sex again. Ever. It's taken a long time to come to terms with that, but now I can say it without crying," he says.

She says Andrew's surgeon is now dead. But Dr. Kennedy, who assessed Andrew's mental fitness, admitted to The Sunday Age: "I don't know if he was ready for it (surgery) or not. He said he was ready for it. He'd been hounding us since he was 18."

Another example of the difficulties of being a detransitioned lesbian:

Below is an example of a famous MtF homosexual male, Alexis Arquette, who became disillusioned with the idea of medical transition:

In 2013, amid increasing health complications, Alexis (pictured left in 2006 with Holly Woodlawn, another pioneering trans actress, who died in December 2015) began presenting herself as a man again, telling Ibrahim that "'gender is bull***t.' That 'putting on a dress doesn't biologically change anything. Nor does a sex-change.' She said that 'sex-reassignment is physically impossible. All you can do is adopt these superficial characteristics but the biology will never change.'" That realization,” Ibrahim suspects, “was the likely source of her deep wells of emotional torment.”

Here are two accounts of detransitioners and how the complications of a difficult past manifested as gender dysphoria. These accounts provide some insight into the difficulty of this experience and why an affirmation model that does not explore the contextual factors in which gender dysphoria manifested is inappropriate and unethical:

She says Andrew's surgeon is now dead. But Dr. Kennedy, who assessed Andrew's mental fitness, admitted to The Sunday Age: "I don't know if he was ready for it (surgery) or not. He said he was ready for it. He'd been hounding us since he was 18."

It's true that Andrew thought he was a transsexual. However, the broken childhood that preceded his referral to the clinic is a recurring theme among those who feel they were misdiagnosed. Born to teenage parents, his earliest memories are of being hit and spat on by his father.

Latching on to his mother, he became distraught when he had to leave her to go to school. Confusion about his sexuality was compounded when he was raped by two men at the age of 16. As he aged and started to resemble his father, he began to hate his male appearance. A chance discovery of a book about a transsexual was a pivotal moment. The story resonated with him. Perhaps this was what he was.

Another former patient, Angela*, was also an abused child. Sexually molested by a cousin between the ages of four and nine, she grew up hating her femininity.

She recalls punching her breasts and working out obsessively at the gym to "remove anything that reminded me I was female". She was a 22-year-old university student when she was referred to the clinic by her GP, depressed and struggling with her identity. Dr Kennedy diagnosed her as transsexual at the first assessment, prescribing her male hormones and suggesting female-to-male surgery

Within months Angela's body was covered in thick hair, her voice deepened and she had a full beard. She had to shave under the covers every morning to hide the truth from her conservative Catholic parents. Two years later she had surgery to remove both breasts and was scheduled to have a full sex change. Angela could no longer conceal the truth from her family and began living as "David". Thankfully, she says, she realised there had been a mistake before undergoing full genital surgery.

"I remember at one point looking at myself in the mirror with this beard, my breasts gone and thinking, 'Oh my God, what the hell am I going to do?' … I felt ugly. I was the classic bearded woman, a monster trapped between two worlds."

She claims her pleas for help were also ignored by the clinic and her return to life as a woman was a nightmare that involved two years of painful electrolysis to get rid of facial and body hair and surgery to reconstruct her breasts…

This study shows that despite reported improved mental health, suicide risk did not improv, illustrating that even with self-reported low regret rates and self-reported mental health, serious problems remain for many individuals.

‘Why didn’t surgery improve the mental well-being of the patients?’

We don’t know and we need more research to answer this question. However, here are a few possibilities:

Possibility #1 – Return to regular life: In their discussion, the authors suggest that there might be an initial euphoria after beginning hormones that wears off. In addition, after surgery, people might be “again confronted with stigma and other burdens.”

In other words, the improvement after hormone therapy is higher than the improvement will be in the end. There is still an improvement later on, but the initial level of euphoria isn’t going to last. If this is true, it would be important information for people who are transitioning so that they don’t have false expectations of what life will be like after transition is complete.

Possibility #2 – Surgery is not the best treatment for everyone: The authors also suggest that further studies should look at exploring the idea that some patients might want hormones without surgery.

It may be that surgery is not the best treatment for everyone with gender dysphoria. Perhaps some people would have been better off with just hormone therapy. Previous studies have found that about 3% of people who have had genital surgery regret it, so we would expect one or two people out of 50 to regret their surgery. Perhaps they are depressed and this affects the group average.

Possibility #3 – Effects of surgery: It is also possible that some people had post-surgical depression and that this affected the results.

Perhaps some people were still recovering from surgery and did not feel well (the study included people 1 to 12 months after surgery). In particular, this might lead to the increase in sleeping problems found in the study.

Perhaps some people were dealing with complications of surgery.

Perhaps the hormonal changes after surgery affected people’s moods.

Possibility #4 – People were already happy: On the other hand, perhaps by the time people get surgery, they are already happy due to counselling, hormones, and social transition.

Perhaps if people had been forced to stop with hormone therapy alone, they would have become unhappy. As the authors point out, it may have made a difference that they knew they were going to be able to get surgery.

Possibility #5 – Surgery doesn’t affect mental health: It may simply be that surgery does not improve mental health. At this point, we do not have proof that it does.

In the end, we just don’t know.

Due to the reality of the outcomes highlighted above, Polly Charmichael expresses that managing expectations is crucial,

It is really important to be checking with people, their expectations of physical interventions as it is obviously true they are not the panacea to all things

We don't really know if this is the right treatment for everyone or whether there are long term implications for this treatment but for families and young people if can be very difficult,' she said of those they help change sex.

'They are seeking certainty, but the reality is at the moment, we don't have certainty.’

One doctor, who must remain anonymous, for fear of losing her job, is planning for increasing regret rates:

Maybe, I say to Dr. K, you are old-fashioned, wrong. Maybe it is fine for a legion of girls to take testosterone, to trade their capacity to orgasm or bear children for a better outward appearance in our highly visual age. Maybe lifelong hormone regimes, molding the body via surgery, breast binders and stand-to-pee prosthetics are progress? “Yes,” she says. “And I hope I am wrong, for the sake of all these young people. But all my instincts as a clinician say not. I’m thinking of opening a practice in a new field: detransition. I foresee a gap in the market.”

This top SRS surgeon admits regret rates are likely to go up with youth transitions:

40% of children who attend GIDS are prescribed puberty blocking drugs. But gender expert Professor Miroslav Djordjevic suggested the rise could be in part a fad among parents who indulge their children.

And of course there is a danger children could regret having treatment.

Prior studies under a more cautious approach to gender transition in adults cannot inform clinical practice with the current cohort of gender dysphoric youth under the current affirmation model. Past rates of regret, from previous studies, also cannot help us understand or predict detransition or regret.

Adolescent-onset of gender dysphoria is a relatively new phenomenon for natal females. In fact, prior to 2012, there was little to no research studies about adolescent females with gender dysphoria first beginning in adolescence [5]. Thus, far more is known about adolescents with early-onset gender dysphoria than adolescents with adolescent-onset gender dysphoria [1, 8]. Although not all research studies on gender dysphoric adolescents exclude those with adolescent-onset gender dysphoria [5], it is important to note that most of the studies on adolescents, particularly those about gender dysphoria persistence and desistance rates and outcomes for the use of puberty suppression, cross-sex hormones, and surgery only included subjects whose gender dysphoria began in childhood and subjects with adolescent-onset gender dysphoria would not have met inclusion criteria for these studies [9–17]. Therefore, most of the research on adolescents with gender dysphoria to date is not something that can be generalized or specific to adolescents experiencing adolescent-onset gender dysphoria [9–17] and the outcomes for individuals with adolescent-onset gender dysphoria, including persistence and desistence rates and outcomes for treatments, are currently unknown. -Littman (2018)

A LCSW expresses the same view and discusses issues with a study used to justify early medical treatment on minors:

The overwhelming majority of the evidence about transition was derived from studies done on adult transitioners. There are only a few studies that look at outcomes among those who transitioned prior to age 18. De Vries et al. noted positive outcomes among pediatric transitioners. However, the sample size of 55 was relatively small. In addition, it seems worth pointing out that the original group being studied consisted of 70 young people. One of these was not included in the study because the individual died from postsurgical necrotizing fasciitis after vaginoplasty. In addition, these young people were assessed for the final time at approximately one year post surgery.

The below screen capture sums up the current cohort of the adolescent females presenting with gender dysphoria, a phenomenon which began in the mid 2010’s.

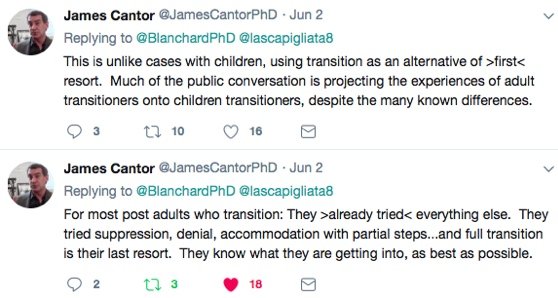

James Cantor, a PhD sexologist, also comments about the flaw in genderalizing from past studies on adults to the children, teens, and young adults who are transitioning now.

James Caspian, a psychoanalyst, speaks to the fact that regret rates seem to be going up with the changing demographics of younger people transitioning:

I’ve noticed a change in the patient group over the last few years. And increasingly, younger people coming, younger people with many more mental health problems and who didn’t fit the kind of profiles that we have seen in the past of the patient. Because the median age of people transitioning at gender clinics used to be around forty one/forty two. And now we were seeing three times as many people in their late teens. (10:31-11:05)

Increases of female teens with serious mental health comorbidities

There seems to be increasing numbers of female teenagers with very serious comorbid conditions or a history of trauma or sexual abuse who are presenting with gender dysphoria

Gender dysphoric girls were on average older than the boys and a higher percentage of girls was referred to the clinic at the beginning of adolescence (> 12 years of age). At the same time, more girls reported an early onset age. More girls made statements about their (same-sex) sexual orientation during adolescence and wishes for gender confirming medical interventions. More girls than boys revealed self-mutilation in the past or present as well as suicidal thoughts and/or attempts. Results indicate that the presentation of clinically referred gender dysphoric girls differs from the characteristics boys present in Germany; especially with respect to the most salient age differences. Therefore, these two groups require different awareness and individual treatment approaches.

A study from Finland also describes the increasing numbers of females and high rates of comorbid conditions.

In Western countries natal male transsexuals exceed natal females transsexuals. A German study demonstrated that the natal male:natal female ratio among transsexual people has changed to more equal towards 2000’s that what it was in earlier decades [16]. However, the over representation of girls on our sample differs still from these more recent trends, and it is similar in both the two Finnish centers. We have so far no explanation for this great over representation of natal girls seen in our material, and equalizing of sex ratio demonstrated by others [13,15,16]. Cultural trends may somehow influence this…

More than three quarters of the adolescent SR applicants had needed and/or currently needed specialist level child and adolescent psychiatric services due to psychiatric problems other than gender dysphoria. Specialist level child and adolescent psychiatric services are provided exclusively for severe disorders in Finland [25,26]. The recorded comorbid disorders were thus severe and could seldom be considered secondary to gender dysphoria.

Lisa Littman’s research on rapid onset GD confirms a similar pattern:

The adolescent and young adult (AYA) children described were predominantly female sex at birth (82.8%) with a mean age of 16.4 years. Forty-one percent of the AYAs had expressed a non-heterosexual sexual orientation before identifying as transgender. Many (62.5%) of the AYAs had been diagnosed with at least one mental health disorder or neuro developmental disability prior to the onset of their gender dysphoria (range of the number of pre-existing diagnoses 0–7). In 36.8% of the friendship groups described, the majority of the members became transgender-identified. The most likely outcomes were that AYA mental well-being and parent-child relationships became worse since AYAs “came out”. AYAs expressed a range of behaviors that included: expressing distrust of non-transgender people (22.7%); stopping spending time with non-transgender friends (25.0%); trying to isolate themselves from their families (49.4%), and only trusting information about gender dysphoria from transgender sources (46.6%).

The GIDS in Britain acknowledges the difficulty in diagnosing these cases of females with mental health problems:

Traditionally, evidence has suggested that those who present to the service after puberty are more likely to continue to request service input for their gender in the long term (Steensma et. al., 2013; GIDS Audit: Retrospective Look at Cases Closed at GIDS, presented at WPATH 2016). However, we see a more diverse profile of young people presenting after puberty (e.g. Kaltiala-Heino et al, 2015), so it is unknown whether this is still the case.

A psychologist reiterates this point:

Dr. Wren: Let me just continue the point. There is an enormous focus on it and, clearly, that is a huge part of our work, so we are also very focused on it, but a recent study from Finland suggested that the sort of complex young people who are coming forward now are going into physical interventions and still having some of the difficulties they had before they went in. We are just very cautious about treating physical intervention for these young people as the royal road to perfect mental health. I think it really needs saying at this point.

This should be concerning, as it appears this WPATH member is seeing more females with regrets. Given the promotion of the affirmation/informed consent model, the removal of any kind of mental health screening for gender exploration in children, teens, and young adults it seems plausible, if not likely, that regret rates will increase.

The individuals below likely transitioned at a younger age.

Cari Stella is a detransitioned female, and lesbian identified. She speaks of her experience with detransition here and her survey results can be found on her blog. This is not a peer-reviewed study but allows for some relevant insights into the complexity of gender dysphoria, the fact that it can resolve even in youth who transitioned post puberty, and the fact that more than half of these young people did not received any mental health counselling (some were not minors, but young when they first transitioned). Provided below are some take-aways from her survey:

59.4% of respondents found alternative ways to cope with their dysphoria.

“117 of the individuals surveyed had medically transitioned. Of these, only 41 received therapy beforehand. The average length of counseling for those who did attend was 9 months, with a median and mode of 3, minimum of 1, and a maximum of 60. I’d like to have something cool to say here, but I’m honestly just stunned at the fact that 65% of these women had no therapy at all before transition.”

Most detransitioners identified as females post transition. In other words, they re-identified with their biological sex and not an alternative under the transgender umbrella, countering the common narrative in the transgender community and that detransition from a trans identity is rare. The positive framing of detransition as a gender journey, or a move from one trans identity to another is something many detransitioners don’t like.

Most of these women were all young (teens and very young adults when they started transition).

The increase of diagnosed females who are medically transitioned as tweens, teens, and young adults will likely lead to more regret. Max, another detransitioned lesbian provides a glimpse the difficulties of transition and detransition.

I transitioned FTM at 16, was on testosterone and had a double mastectomy by 17. I’m 20 now and back to understanding myself as a lesbian, like I was before I found out about transition and latched onto it as a way to “fix” body issues created by the challenges of growing up in a deeply misogynistic and lesbian-hating world.

I absolutely am traumatized by what happened to me, and I’m not the only one. I’m a part of support networks for women who stopped transition that have over 100 members, and that’s just the individuals who have gone looking for others with this experience and found us. I’ve met more than a dozen of these ladies in person at different times… we’re definitely real.

Plenty of others who transition, whether they continue or not, live with complicated feelings about what happened. Not all of us name those experiences the same way, search for community to process that pain, or ever “go public” to any degree. This is trauma.

Hormone therapy really wasn’t that safe, in my experience. I remember being 17 and watching my pediatric endocrinologist literally Google dosing information right in front of me. Didn’t inspire confidence. The doctors controlling my HRT had no idea what they were doing, at least with patients like me. They were all just as confused about how to treat me medically as they were about how to interact with me as a human being. When I was on testosterone and taking Adderal for ADD, I got heart palpitations, chest pain, and shortness of breath. I didn’t tell anyone because I didn’t want to have to choose between a psych med that was making a huge difference in my ability to function in the workplace and hormone therapy, and I didn’t want to acknowledge that what I was doing was dangerous.

Early in my transition, I went through menopause. This caused vaginal atrophy and drip incontinence that has persisted for years. I piss myself slowly all day now; it’s really not cute or fun. I refused to acknowledge it was connected to the HRT-caused vaginal atrophy that immediately preceded its onset until months after going off testosterone. Yeah, I signed a paper saying I knew that could happen. I also thought this treatment was my only hope for coping with the intense feelings of alienation/disgust with my femaleness. I was wrong. Transition didn’t help. It did harm, harm that I now have to learn how to live with on top of all the shit I thought transition would fix.

James Caspian has been working with transgender clients for years and is becoming very concerned with the numbers of young females transitioning.

So, we’re are seeing more and more of young women who had identified as lesbians, identifying as an alternative gender identity, wanting to have double mastectomies without any other treatment. And there have been cases of people in that group who have then regretted it. And some of whom have then taken their doctor to court as well, because they have regretted their treatment and they felt the doctor shouldn’t have let them…in the US and the UK as well. (8:50-9:20)

Efforts to deny regret and detransition:

With the seemingly increasing rates of detransition there have been many insightful blogs written by detransitioners (see here). There is a strong desire of trans activists, including activist mental health and medical professionals, to paint all cases of detransition as 1) Regret only occurs because society marginalizes these people makign it difficult for them to live within our society or 2) that despite detransition, they still remain a form of trans. This in contrary to most of the stories of the detransitioners who speak out about their situation online. They have returned to their pre-transition selves and often feel very critical of aspects of trans ideology.

In the above detransition survey provided by Cari, the response a WPATH clinician was to deny that detransitioned individuals were ever trans, despite the fact that WPATH has acknowledged gender fluidity. By negating that these individuals identified as transgender and was treated using WPATH’s affirmation model, such clinicians are avoiding any responisibility.

Here Johanna Olson-Kennedy (on a delinked podcast) pushes the narrative people only detransition due to lack of trans acceptance.

Absolutely. [they both laugh]. That’s better than a lot of surgical interventions. And I think that even among the people that have, sort of, regretted that decision, it has to do not with that they have gender instability but that they were doing this whole physical or phenotypic gender transition in adulthood and they had an entire life in one gender role that they then lost. And that would be cause for regret I think for anyone, who lost everything in their life because they were pursuing their authentic self.

But the more recent narratives of detransitioners, don’t conform to that model at all. Below is a screen capture of a detransitioner who is very upset about the negative consequences of his experience in the trans community and its extremely intense identity politics.

C. Conclusion regret rates

The fact that people are willing to go through these harsh, risky treatments is testament to the reality of gender dysphoria. In assessing the probability of transition regret and detransition, it is important to note that older studies primarily were done on people who transitioned in middle age (often males). Currently tweens, teens, and young adults are medically transitioning and often have non-binary identities, rather than a strong desire to be the opposite sex. Thus, three factors must be acknowledged: 1) the age of the current cohort seeking transition, 2) the natal sex and 3) the transgender identity from binary transgender to non-binary. There are hundreds of thousands of videos supporting medical transition and non-binary identities for young people on social media platforms. Young people document all of their surgical procedures as a rite of passage. Further, WPATH and the medical community support these experimental treatments, regardless of having no long-term data.their

If all of these young people will ultimately be happy, the social networking and online visibility is all a good thing. Since transition rates are increasing for very young individuals it is unknown what the regret rates will be and what the impacts of having very young bodies put on cross-sex hormones for a lifetime will have on their health. Past transition statistics on regret will not likely translate to younger people transitioning in larger numbers now with many more females transitioning with mental health problems. Regret rates are very likely going to go up. It’s just a matter of how much.

Transition helps but is not a fix all either. For this reason, one MtF (and other trans people) support a mental health model:

Through talking to other trans people in my life, it has become apparent to me that transition surgeries are an answer but not the answer to the long-term health and well-being of gender dysphoria patients. Unfortunately, many trans people get so fixated on surgery for so long, that they may forget that there is more to life and transitioning than just surgery and other medical intervention. The fixation is often driven by the fantasy that surgery, and transition in general, will transform them into a new person, and that all the problems in life will go away…

The availability of surgery isn’t the issue nor is removing barriers to surgery; the issue is that trans people are being educated and socially encouraged to abandon a holistic and forward-thinking approach to life. A return to medical gatekeeping, albeit modernized, for the treatment of gender dysphoria would be in the best interest of trans people. This just might slow down transgender contagion, the unhealthy and socially-sanctioned fixation with gender.

Dr Wren of Tavistock:

We have shifted to make the treatment available earlier and earlier. But the earlier you do it, the more you run the risk that it’s an intervention people would say yes to at a young age, but perhaps would not be so happy with when they move into their later adulthood

© Gender Health Query, 6/1/2019

REFERENCES FOR TOPIC 8

Updates Topic 8

CONTINUE TO TOPIC 9:

How will reinforcing gender dysphoria in children affect desistance rates & young people?

CONTENTS

8) Regret rates & long term mental health

A. Despite low regret rates, mental health problems remain high

B. Are regret rates increasing with more transitions & people transitioning at younger ages?

-Regret rates appear to be increasing

-Increases of female teens with serious mental health problems

-Efforts to deny regret & detransition

BACK TO OUTLINE

More

1. Do Children Outgrow Gender Dysphoria?

3. Are children & teens old enough to give consent?

4. Comments safety / desistance unknown

5. Gender dysphoria affirmative model

6. Minors transitioned without any psychological assessments

8. Regret rates & long term mental health

11. Why are so many females coming out as trans / nonbinary?

13. Why is gender ideology being prioritized in educational settings?

14. Problems with a politicized climate (censorship, etc)